When Yongjian Chang built North American Plants in 1998, the company had 800 square feet of lab space to propagate plants through a process known as tissue culture — essentially cloning them to meet nursery demand for ornamental trees and shrubs.

It’s come a long way in the years since, with five expansions bringing lab space to some 23,000 square feet and a switch in 2006 to focus on berries and rootstocks for tree fruit and nuts.

Today, North American Plants produces 3 million blueberry, blackberry and raspberry plants and 10 million rootstocks for tree fruit and nuts annually.

Increasing demand for disease-resistant rootstocks, particularly in the apple industry, has the company poised for another change: selling directly to growers who want to reduce the wait time and get trees in the ground sooner.

For the first time, North American set up shop during December’s Washington State Tree Fruit Association’s Northwest Hort Expo in Wenatchee, Washington, to explain the process to growers and to take orders.

Chang views the move as an opportunity to expand his market, sure, but also to help speed the process of getting trees into the hands of growers, namely those establishing nurseries on their own farms.

“In the beginning, I really thought I would just be selling to stool bed nurseries, but the demand is so much quicker than they can meet,” Chang said. “If the growers buy directly from us, that’s really much more efficient for everybody on this scale, as long as they are able to handle these trees. Large growers certainly can.”

Tom Auvil, research horticulturist for the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, agreed. “It provides a whole different opportunity to get access to plant materials that are oversold for the next three to four years. Growers can short-circuit that backlog by learning how to farm them,” he said.

However, he said he also encourages people to consider the small, green-leafed tissue culture plants more like tomato transplants than apple trees. “They take a lot of care,” Auvil said.

The rootstock nurseries, mainly in Oregon, already have been selling to growers directly, and the fact that they can now get them from a tissue culture facility as well likely won’t change that, said Bill Howell, manager of the Northwest Nursery Improvement Institute.

“There’s a lot of demand, that’s for sure,” he said.

He agreed, though, that the product is different. “Growing a nursery tree, it’s not easy. And the growers who take it on are carrying that extra duty and getting their own tree,” he said. “For a grower to do it, it requires them to become a little more diversified, because instead of just growing a fruit crop, he’s now growing a vegetative crop.”

Tissue culture history

Chang didn’t particularly like plants as a child, but as a university student in China’s Heibei Province in the Beijing area of north China, the government assigned him a career based on his aptitude tests.

“At the beginning, I didn’t like it,” he said, laughing. “After I got my degree I thought I would never touch it. Unfortunately — or fortunately — I have been working on it all the time since.”

Now, it’s his passion.

“He is always walking through the greenhouse, looking at the beautiful green plants, and he is so happy,” said Shirley Feng, a biologist at North American. “Now, he has passion for the plants. You can see the smile. The combination of love and the ability to make money has worked well for him.”

Tissue culture techniques have been around for many years.

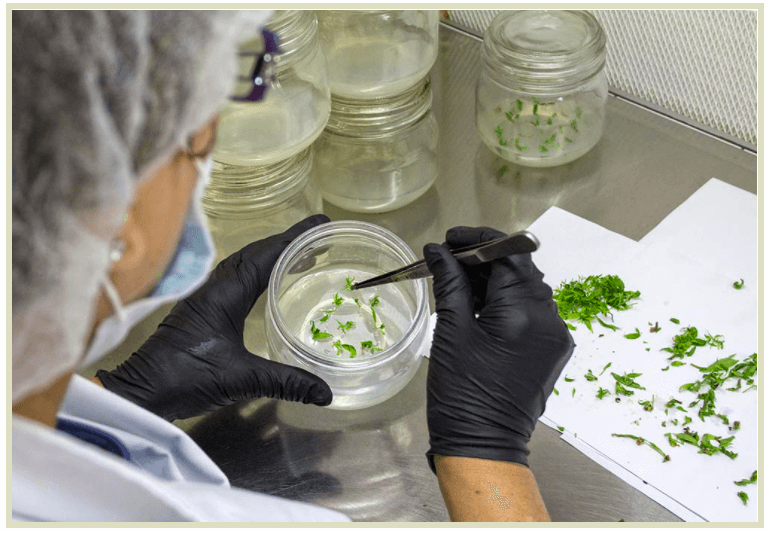

Given the proper nutrients and plant hormones, pieces of leaves, stems or roots can often be used to generate a new plant.

The plant material is generally separated with a fine scalpel into roughly 1-inch growing tips in aseptic conditions to protect against pathogenic microorganisms, and the tissue cultures are grown in sterile conditions with the proper media.

Selecting the correct stock material for micropropagation is the first step, requiring clean material and a carefully crafted media recipe for the culture process.

Once workers know they have clean material and a proper recipe, plants are multiplied in the laboratory — a process that shows the efficiency and power of micropropagation. From one shoot, within 12 months, North American can produce 400,000 plants.

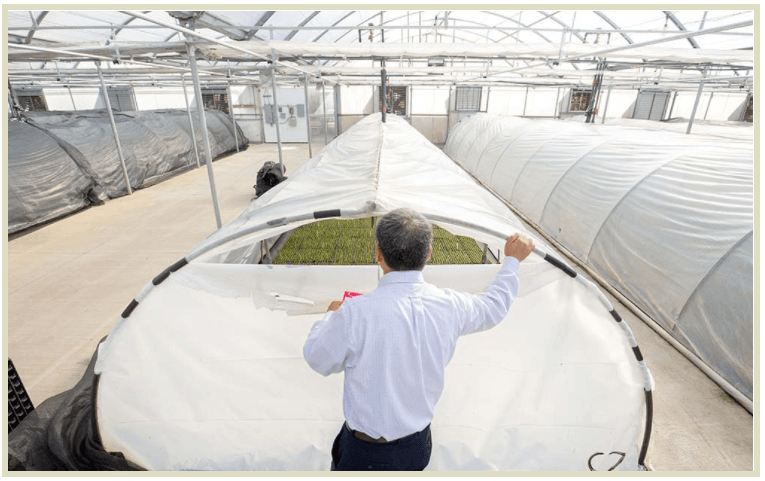

Workers then root the plants, some in the lab and some in the greenhouse, depending on the crop, before moving them to acclimation hoops, where the temperature, humidity and light density are carefully controlled.

“These three factors have to be under control, otherwise, in 5 minutes, with these small cuttings, they can stop growing,” Chang said. “They can shut down quickly.”

The acclimation process generally takes three to five weeks, depending on the crop, before the plants are moved to the growing greenhouse to grow bigger for shipment.

Last year, North American Plants sent 8 million plants to customers in April, May and June alone. The company supplies to nearly all of the major nurseries in the U.S. from its base in Oregon’s Willamette Valley — apples, pears, cherries, peaches and nectarines, as well as avocados and nuts to meet demand in California. It employs as many as 170 full-time workers in the busy spring months.

For apples, Chang only produces the fire blight-resistant Geneva rootstocks, which “for sure have a great future, but it’s such a rush to get them out. It’s so quick, it’s dangerous,” he said. “Some people are planting the same age of trees as the rootstock trial. They are really good rootstocks, but we still have a lot of things to learn.”

One of the more challenging rootstocks in liner beds — Geneva 41 — remains tricky to propagate through tissue culture, and takes much more work to produce. While many rootstocks can multiply at a 1-to-3 ratio, G.41 is probably closer to 1-to-2.5.

Pushing that rate increases the risk for mutations. “There isn’t any lab that can 100 percent guarantee plants without mutations, but we can control for that,” he said. “We do everything possible — from media recipe, culture environment, anything that could sync up back to mutation — to try to reduce the chance.”

Tips for growers

Several large orchard companies have turned to tissue culture labs to get access to fire blight-resistant rootstocks, Auvil said. He encourages others to consider it, with care.

“They’re sensitive to drought, too much sun, too much cold, too much wind. But mostly, it’s water,” he said. “The No. 1 issue is getting water to the tree.”

Moving the trees from a greenhouse to direct field conditions without adequate irrigation can drought-stress the plants, causing margin burns on leaves or dropped leaves, until the trees are able to establish their root system.

Some people are more careful the first year and won’t make any mistakes, Chang said. “But normally, after one year, everybody can learn.”