An olive oil campaign between light, shadows... and many questions

The 2024/25 olive oil campaign began under a sky full of climatic doubts, rushed decisions, and unstable prices.

If the situation accompanying the beginning and development of this campaign can be defined in one word, that word would be: uncertainty — uncertainty that began when no clear signs of a stable production appeared, one that could bring some calm to what has been the most atypical pricing situation I can recall in all my years in the olive oil industry. There have been similar moments before, but never of this magnitude.

Everything that preceded and surrounded the beginning of this campaign has been atypical, starting with the climate — 1.1ºC above the annual average (reference period 1991–2020). It was the third warmest year since the start of records in 1961, only behind 2022 and 2023. In fact, the 10 hottest years in history belong to the 21st century. And the climate plays an essential role in the global production of any crop, and the olive grove is no exception.

The olive tree produces during the vegetative growth of the previous spring — what we call the olive tree’s biennial cycle. This growth occurs generally from March to mid-July, and during this time the buds destined for production form, which should then become flower clusters and eventually olives. But this depends on the stimuli the plant receives between June and October — stimuli related to several factors: climate, chilling hours, heat hours, the timing and intensity of those hours, nutritional reserves and their balance, water stress… and also how late the previous harvest was, how much fruit the olive tree was carrying at the time of that harvest, and therefore what was the level of assimilates extracted by those olives — and we could go on with other factors.

Everything pointed to the idea that if the 2023/24 campaign had been short in production and in the medium/high range of oil yields, then the 2024/25 campaign should be a good one. But this year’s adverse and atypical weather brought a sea of doubts, doubts that only began to fade by mid-September.

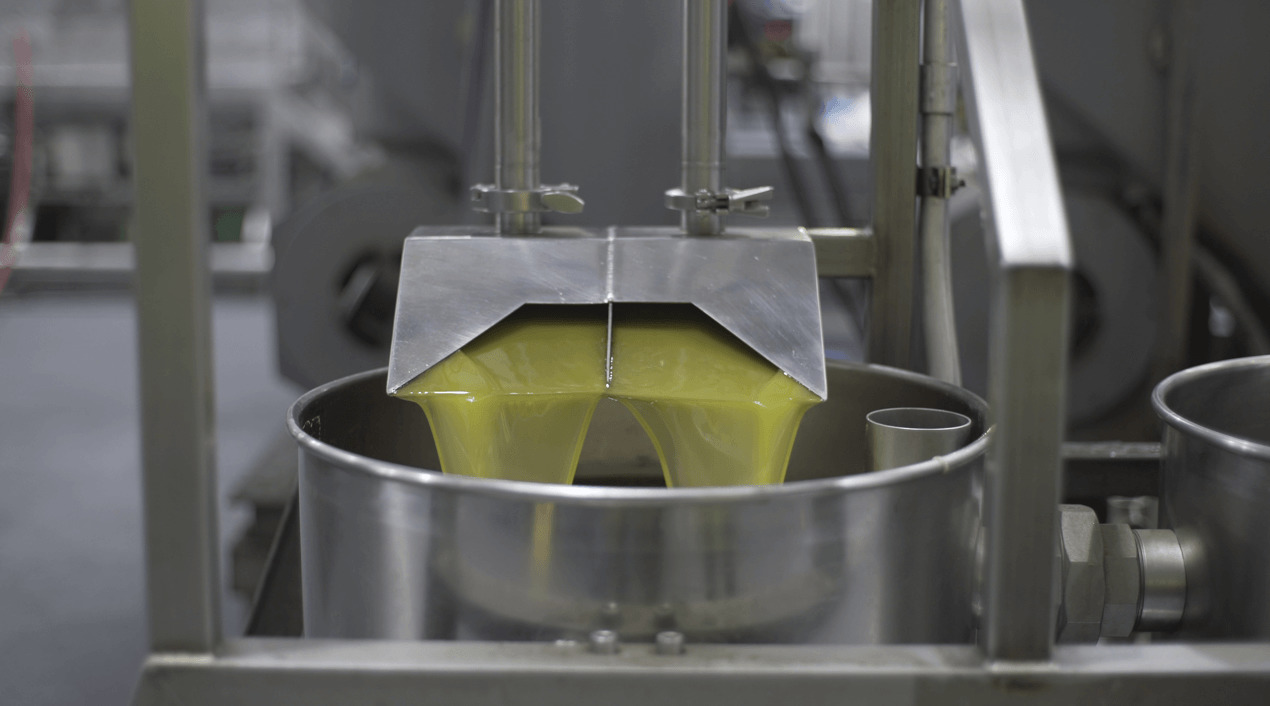

In September, we started collecting the first olive samples to determine the stage of lipogenesis and thus figure out when the campaign would start. These early samples indicated that fruit ripening was not ahead of schedule, and all the data we collected throughout September and October suggested that we needed to be patient — oil yields were abnormally low.

Patience is another aspect blurred by the influence of the high prices that had been dragging on all year. The rush to harvest and make deals at high prices led some to begin harvesting. But they quickly realized that such low yields could not sustain economically viable returns for those olives. Moreover, another factor emerged — one that confirmed that patience is a good travel companion in these situations. Early oil quality analyses revealed that the chemical formation of the oils was incomplete — the formation of many chemical compounds such as sterols, fatty acids, phenols… were all seriously compromised by the rush to harvest, blinded by the idea of getting the highest possible price or even being the first to have oil ready to sell. But for everything, there is a right moment — and that moment had not yet arrived.

Only the oils intended to compete for organoleptic recognition in the many, varied, and sometimes even puzzling competitions started to appear. These are mainly produced from early to mid-October through mid-November, depending on production zone, variety, climate, etc. The resulting price affected by yield also played a role, as it was not unusual to see oils during this period with yields below or around 9%, which logically led producers to limit the quantities produced.

Indeed, these low yields continued even through the end of November and remained significantly below the average of recent years — by up to 2 or 3 points — which meant that the campaign’s main harvest started mostly in December.

The “uncertainty” about how prices would behave was the dominant mood. Producers, hoping prices wouldn’t fall, argued that no one should rush, that production might not be as high, and that consumers had accepted that the value and quality of olive oil was worth the price, and therefore were willing to pay more. So there was no reason to drop prices. But a crushing reality took over. As olives flowed steadily into Spanish mills — without a single rainy day to slow things down — the harvest was soon expected to be good. This triggered a steep price drop. Most producers began pushing forward, offloading inventory and closing contracts clearly below €6, then below €5, €4, and even €3 for lower-quality oils. And now, in April, all prices have clearly repositioned below €4 — and we’ll see how things go once flowering for the next campaign becomes visible.

Had we focused on quality, prices might have held up a bit better, since with slightly lower yields there would be less supply on the market. But that remains a utopia, or perhaps just a dream of mine.

Spring is now arriving, and March has been exceptionally rainy — the rainiest in history — yet another anomaly confirming that everything remains marked by uncertainty. But as things stand in Spanish olive groves, the 2025/26 harvest should be exceptional — not only in Spain, but across the Mediterranean region. This could lead prices to reposition — or maybe not. Only time will clear up these doubts.

I used to ask my grandmother María quite often about the weather, the olive harvest, and what might happen depending on this or that. And she, very wisely, used to say: “Maño, if you want to know if it’s going to rain tomorrow, ask me the day after. And if you want to know if we’ll have oil this year, wait until it’s in the jug — in the one at home, not the one at the mill — and then you’ll know.” My grandmother was wiser than a saint.

Everything can change until it’s truly done. So we must not rush into any kind of decision. Everything in due time. Otherwise, we create “uncertainty”, we jump the gun, and we trigger disorder and mistrust in the market — our everlasting unfinished business.

Fortunately, this year we’re starting to see fresh, new shoots — born of new varieties that are emerging strongly, generating renewed hope and excitement among producers and also among the most demanding consumers. Varieties like I-15, Sikitita 2, Florentia, Coriana, and above all Lecciana — a variety that many call “the absolute one” — are emerging with force in the high-quality oil market. We’re not going to place the entire responsibility of revitalizing the olive oil sector on their shoulders, but they do open new doors for exploring new horizons in premium oil production.

We just need to be patient, apply sound technical criteria without rushing, and let time dissolve any uncertainty surrounding their physical, chemical, and sensory potential.